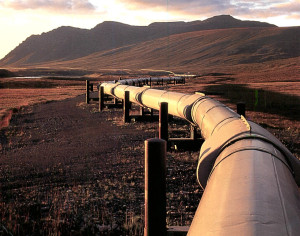

The proposed TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline would bring energy-intensive oil from Canada’s tar sands through South Dakota, increasing the risk for oil spills, natural resource degradation, and further allowing our dependence on oil to impact climate change. The potential damage to communities impacted by Keystone XL extends beyond the environment and economy; the pipeline will bring an influx of temporary workers through rural American Indian communities. We have already seen evidence of this in neighboring state North Dakota, where drilling in the Bakken Shale Formation has brought not only money, but drugs, violence, and pollution of tributaries from over a million gallons of spilled fracking water, which threatens both tribal drinking water and tribal peoples. Twenty-five percent of onshore oil and gas reserves are located on Native American land, and one of the largest booms in the country is happening on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota.

In the height of Fort Berthold’s boom, oil extraction has brought money and jobs to North Dakota and improved the economy, but has also ushered in many unintended consequences. In the last three years, North Dakota’s population has grown three times faster than the population of the United States and the percentage of drug-related crimes has doubled. The oil boom areas of the state were not built to handle the influx of the workforce. What was once a peaceful, sparsely populated area now sees the highest traffic fatalities in the nation, 51 percent of which are alcohol related, and the influx of money has brought new complex challenges to the reservation. In Williston, ND, a town that has swelled with over 21,000 temporary workers in the last five years has seen theft, abduction, violence, domestic abuse, and sex crimes triple since the explosion of oil exploration has risen from the plains.

The TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline would house pipeline builders in three rural ‘man-camps’ near reservations in South Dakota, housing approximately 1,000 workers per camp. One of these man camps would be in Colume—a community with a substantial Native American population that is about 10 miles away from Winner, SD—and adjacent to Rosebud Reservation. Winner’s mayor Jess Keesis does not believe there will be long-term negative effects on the community during the 14-month pipeline building process, but a study found that crime had risen more than fivefold in booming oil communities in North Dakota and Montana.

In South Dakota, the state with the second highest incidence of rape in the country, forty percent of victims of sexual assault are American Indians, though they make up just 10 percent of the population. According to the Justice Department, one in three American Indian women has been raped or experienced an attempted rape, and just 13 percent of sexual assaults reported by American Indian women end in an arrest. In other words, American Indian women are 2.5 percent more likely to be victims of sexual violence than other races of women, and the perpetrators of this violence are frequently non-Native. When crimes are committed on reservation land by a non-Native person, the tribal court is left powerless because they cannot prosecute non-Native persons. The increase of drugs, crimes, and sex trafficking has left residents feeling unsafe on the nearly one million acre Fort Berthold Reservation, which is patrolled by only 25 officers as of October 2014.

In addition to drug and traffic incidents, NDSU Extension agents observing the North Dakota oil boom have noticed an uptick in the number of domestic violence reports and registered sex offenders in these oil communities. District of South Dakota U.S. Attorney Brendan Johnson has also spoken about his opinions on the increased opportunity for prostitution and sex trafficking where there is a large gathering of men, particularly referring to South Dakota’s hunting and tourism industries. A strong population influx, combined with existing prejudices and a general historic ambivalence toward American Indian rights during land and economic development in South Dakota, suggest an increased potential for sexual violence. Is economic gain more important than the safety of South Dakota’s vulnerable populations in and around the state’s Reservations?

Opposing this pipeline is not only about the environment and ensuring a healthy future for our country; it is also crucial to consider further the negative impacts this economic development project would have on vulnerable populations such as our women and children. Oil can pump money into communities and to American Indian reservations, but the consequences in many communities, though unintended, have been vast and harrowing. As a South Dakotan, a farmer, and a woman, I urge President Obama to deny Keystone XL their permit to build this pipeline through our nation’s farmland, our prairies, and our future.

Keely Gerhold is an MPA Candidate in Public & Nonprofit Management & Policy at New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and is from Castlewood, South Dakota.