By Sarah Wattar

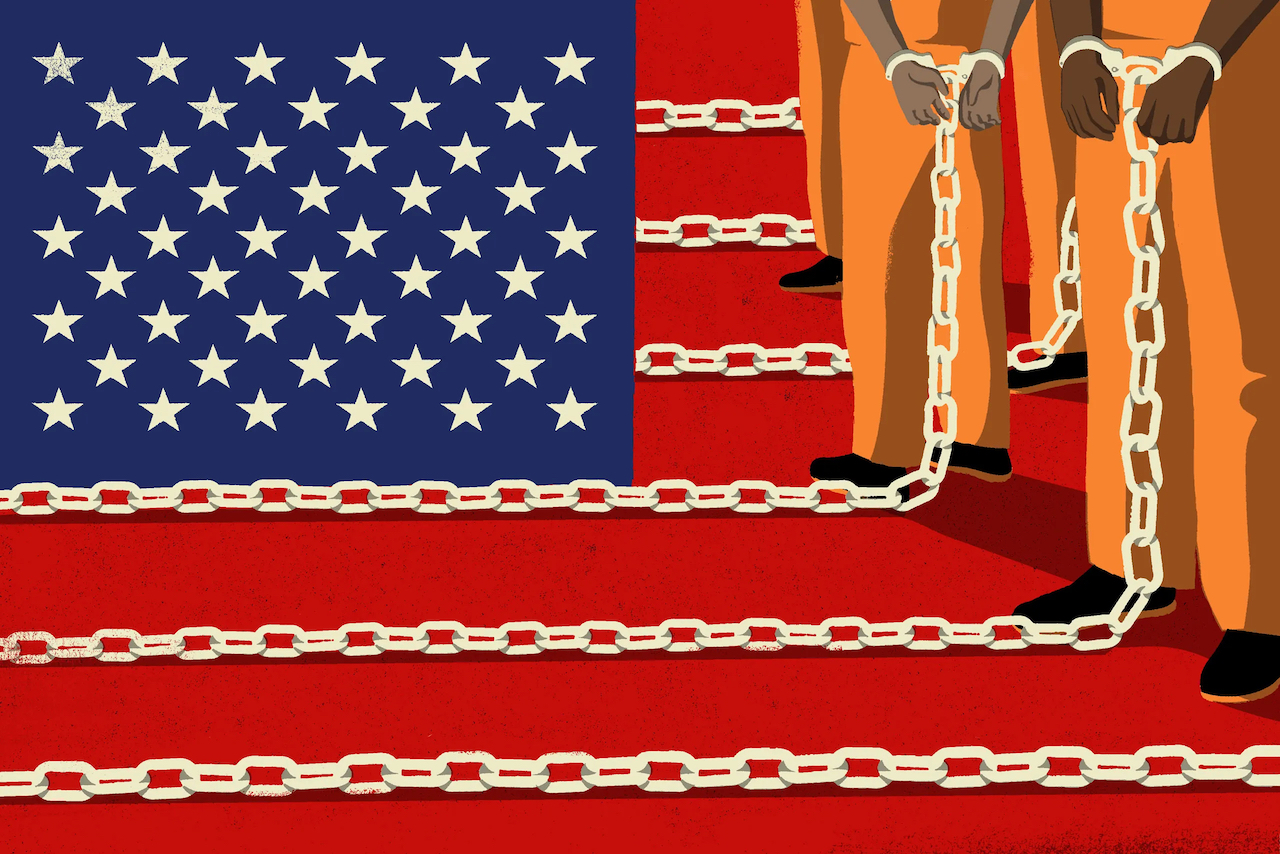

Earl Washington was nine days away from his execution when an attorney secured a “stay of execution,” meaning a delay or hold. 22 years later, DNA evidence exonerated him and the actual perpetrator confessed. According to the Innocence Project, since 1989, over 3,200 people have been exonerated in the U.S., 375 through DNA testing—21 of whom were on death row and 44 of whom pleaded guilty. They have collectively served over 27,200 years in prison. 53% of exonerees are African American. 69% of their cases involved eyewitness misidentification. 43% involved misapplication of forensic science. And 29% involved false confessions—meaning 102 people confessed to crimes they did not commit. How can this country pride itself on being “the land of the free” when so many of its people are not?

While it may be easy to dismiss these cases as genuine accidents on the courts’ part or to think it is absurd to confess to something you did not do, it is important to acknowledge the patterns in these cases. “We the people” need to learn how our system works, revise it where it does not, dismantle it where it harms, and deter further mistreatment of all those who make up “the people.” There are attempts at remedying wrongful convictions through expanding Conviction Review Units (CRU), which reexamine convictions and advocate better practice to avoid future mistakes. There are approximately 95 CRU’s operating across the country out of more than 2,300 prosecutor’s offices, and while they’ve helped secure 60% of exonerations alongside other cooperative organizations, I believe this is only a band aid solution that cannot keep up with the masses of people incarcerated daily.

Instead, we should direct our attention to the root cause of wrongful convictions: prosecutorial misconduct. Prosecutorial misconduct involves people in positions of power carelessly or purposely disregarding truth, evidence, or circumstances and perpetuating wrongful convictions. And in many cases, evidence is created out of personal desire to attain a conviction. Prosecutors and judges are, in many states, elected to these positions. These legal actors often seek a public reputation of being “tough on crime,” and as a result, they are incentivized to have a “win at all costs” mindset.

In fact, prosecutors are so determined to increase their number of convictions as rapidly as possible that they wield the threat of longer sentencing should a defendant decide to use their right to a fair trial instead of accepting the plea deal the prosecutor offers. A plea bargain is a deal a prosecutor offers a defendant before trial. The logic is clear: plead guilty and receive a sentence of five years in prison, or go to trial and risk a lifetime prison sentence? One might ask, if you are innocent, why accept a plea deal? Imagine being told you would have to sit in jail for six months or a year or two waiting for trial if you could not afford the thousands of dollars in bail fees. Or imagine facing a lifetime of prison, going up against the State and all its resources, and dealing with the possibility of losing at trial (which, statistically speaking, they most likely will). A harrowing reality: about 97% of convictions across the U.S. —both at the federal and state levels—are resolved by a plea bargain.

Let’s consider a situation in which a defendant is confident enough in the strength of their case and in their innocence to reject a plea bargain deal. Prosecutors, detectives, and law enforcement hold immense power over a person of interest before a trial has even begun. These legal actors, for many years, have lied, bullied, and physically trapped their person of interest at their leisure. Prosecutors are administrators of justice; their “primary duty is to seek justice within the bounds of the law, not merely to convict”. However, they often ignore their ethical duty to pay attention to factors like the mental health of the defendant, and instead try to manipulate information into an admission of guilt. It is important to note that over 50% of currently incarcerated people suffer from mental illness. Vulnerable people, such as those affected by mental illness, are especially in danger of wrongful conviction, poor treatment and accommodation in facilities, and the likelihood of failure for adequate defense and post-conviction appeal success. For example, twenty-two year-old Earl Washington had an IQ of a 10-year-old child. He was manipulated through his interrogation into false confessions despite the fact that law enforcement could see that he had the facts of the case wrong. What he confessed to was inconsistent with the actual crime circumstances, and yet law enforcement ignored this and used Washington’s desperation to leave the interrogation to convict him.

Additionally, prosecutors will often withhold evidence; participate in destroying, concealing, or fabricating evidence; elicit perjured testimony; make improper and inflammatory statements; and ignore obvious red flags of innocence to win cases. They act with nearly complete impunity and no accountability for their actions. While there are existing legal remedies to prosecutorial misconduct, the burden of proof lies with the defense. To provide an example, the defense would have to prove that the prosecution purposely and knowingly withheld the evidence of innocence or that the misconduct surely affected the outcome of the trial. This can be nearly impossible. The only way to remedy prosecutorial misconduct, in the status quo, is if judges in the circuit courts, appellate courts, or supreme courts agreed that there was purposeful misconduct and that it had a significant impact on the trial. Prosecutors have almost complete legal immunity. There has only been one prosecutor ever imprisoned for illegal actions that led to a wrongful conviction, and this particular prosecutor’s sentence was for 10 days (but he only served 5 days due to good behavior). The system has willfully ignored for years the countless prosecutors who have withheld evidence that would have proven the innocence of people on death row. Therefore, I would argue that these prosecutors should be held accountable for what is essentially attempted murder. And yet, prosecutors seem to be excluded from “the people” bound by the law; they break the law constantly, lying and cheating, and hundreds of thousands of people are losing their lives and loved ones because of their misconduct. And there are numerous legal loopholes that allow them to act above the law, above all other citizens, and I strongly maintain that this immunity must end.

Although the U.S. only comprises five percent of the world’s population, it has 25% of the world’s prisoners. There are currently over two million people incarcerated in the United States—the highest number of incarcerated persons in the world. U.S. federal and state governments spend sixty billion dollars annually on incarceration and spending continues to grow. However, I would assert that the real criminals are the ones running the show—proven prosecutorial misconduct comprises over 700 wrongful convictions. And those are ones that we are aware of, let alone the thousands that have been claimed but not yet substantiated. A DA’s office does not want to admit that a mistake has been made and prosecutors will quite literally argue to their death that they had properly convicted the right criminal despite the evidence that proves otherwise.

I believe, and I think that many would agree with me, that no one, especially prosecutors, should be allowed to break the law and harm people in such extreme ways just to look good in their own reports. Citizens need to be made aware of the frequency of prosecutorial misconduct and the depth of its harm on “the people”, and we must act now to bring forth legislation to eliminate loopholes that allow prosecutors legal immunity when they break the law. Imagine, for example, if we one day declared that a prosecutor who has participated in a wrongful conviction must spend the same amount of time in prison as the person they wrongfully convicted. People would argue that policies to curb legal immunity would result in prosecutors being much more hesitant to convict, and I would maintain that is exactly the objective. Prosecutors must be sure, beyond any reasonable doubt and with inarguable evidence, that a person is absolutely guilty upon conviction. The presumption of innocence until proven guilty must hold its weight. Currently, once one is charged, they are doomed and declared guilty by the prosecutor and their office. A jury is told by law enforcement, the people they are taught to trust all their lives, that this person is guilty. These courtroom dynamics are harmful, and prosecutors should instead be afraid of convicting an innocent person and willing to accept responsibility in the event that they are wrong. They are effectively playing with the notion of taking someone’s life. They create immeasurable trauma, and they should have to proceed with caution when exercising their power in law and be held accountable when they are in the wrong.

I will leave you with an illustrative metaphor. To try to make your way out of a wrongful conviction is like trying to catch your breath as someone holds your neck under water. It is time that we notice the desperate bubbles, remove the murderous hands, and pull our people, our fellow citizens whom are drowning in incarceration, out of the darkness. Oh, and let’s not forget to charge those murderous hands with attempted murder.

Sarah Wattar is a student at the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. She was a former high school English literature teacher, and worked in international schools in 4 countries—the UAE, Portugal, Vietnam, and the United States. She is now studying Global Public Policy in a joint EMPA program with University College London (UCL) in London.